Censorship

Click to Read Article

Censorship is enacted through legislation and aims to protect the status quo,

often under the justification of safeguarding public safety, social harmony, or national

security. Recent legislative measures, such as Bill C-11, Bill C-18, and Bill C-64, raise

concerns about government overreach, media control, and suppression of dissenting

voices. While policymakers argue that these laws safeguard democracy by combating

misinformation and ensuring fair compensation for news outlets, critics contend that

they primarily serve elite interests, limiting access to diverse viewpoints and

undermining democratic engagement. Canadian citizens are frequently misinformed by

corporate-controlled media outlets, which prioritize elitist interests and, in doing so,

undermine democratic engagement and public discourse. Journalists are subjected to

enable elitists to drip-feed their agendas to the Canadian population unless they want to

lose their jobs. Recently, the shift in social media's popularity has displaced news media

and annihilated what we see regarding the new censorship legislation, the elite panic of

losing their mass narratives. While passing these legislations to maintain their elite

agendas, they are violating their country's citizens' fundamental human rights.

Throughout this essay, the reader will be guided through contemporary debates

on censorship, following legal frameworks and key legislation, and the history of

censorship to better understand censorship as we know it today. This examination aims

to answer the question: What is the Canadian government's true motive for putting forth

legislation on censorship?

Contemporary Debates

In this section, we will look at a few contemporary debates regarding censorship

issues: (1) The New Censorship, (2) Regulating Online Content, and (3) Government

Regulations.

The New Censorship

Christine Van Geyn (2024), a Canadian constitutional lawyer, says there is an

uprising of new censorship empowered by the government through legislation and

regulation, which is used to stomp down dissenting viewpoints. These are done through

professional private regulating bodies to whom the government gives authority.

Professional regulators oversee all fields, such as law, healthcare, education, psychology,

etc., and are empowered by the government through legislation. Canadians in regulated

professions need the government's permission to do their jobs. That permission is

granted by these self-regulating professional bodies that have their own sets of rules and

discipline. Geyn explains that professional regulators are subject to the Charter of

Rights and Freedoms when making their decisions and must only regulate off-duty

speech in the public interest. However, there have been cases when regulated

professionals off-duty express their personal ideas or beliefs and are subsequently

disciplined.

An example is Dr. Jordan Peterson, who used social media to express his views

on various political, social, and cultural issues. The members of the public had strong

opinions about his views and filed complaints to the College of Psychologists of Ontario,

where he was subsequently disciplined. A problem is raised because “the result is that

professionals who express unpopular views are disciplined, regulators barely glance at

the Charter, and courts are deferential when they review that discipline” (Geyn, 2024).

Regulated professionals still retain their freedom of expression, a constitutionally

guaranteed right under Section 2(b) of the Charter. However, regulators punishing

professionals off-duty because of their views that are shaking up the status quo is

problematic.

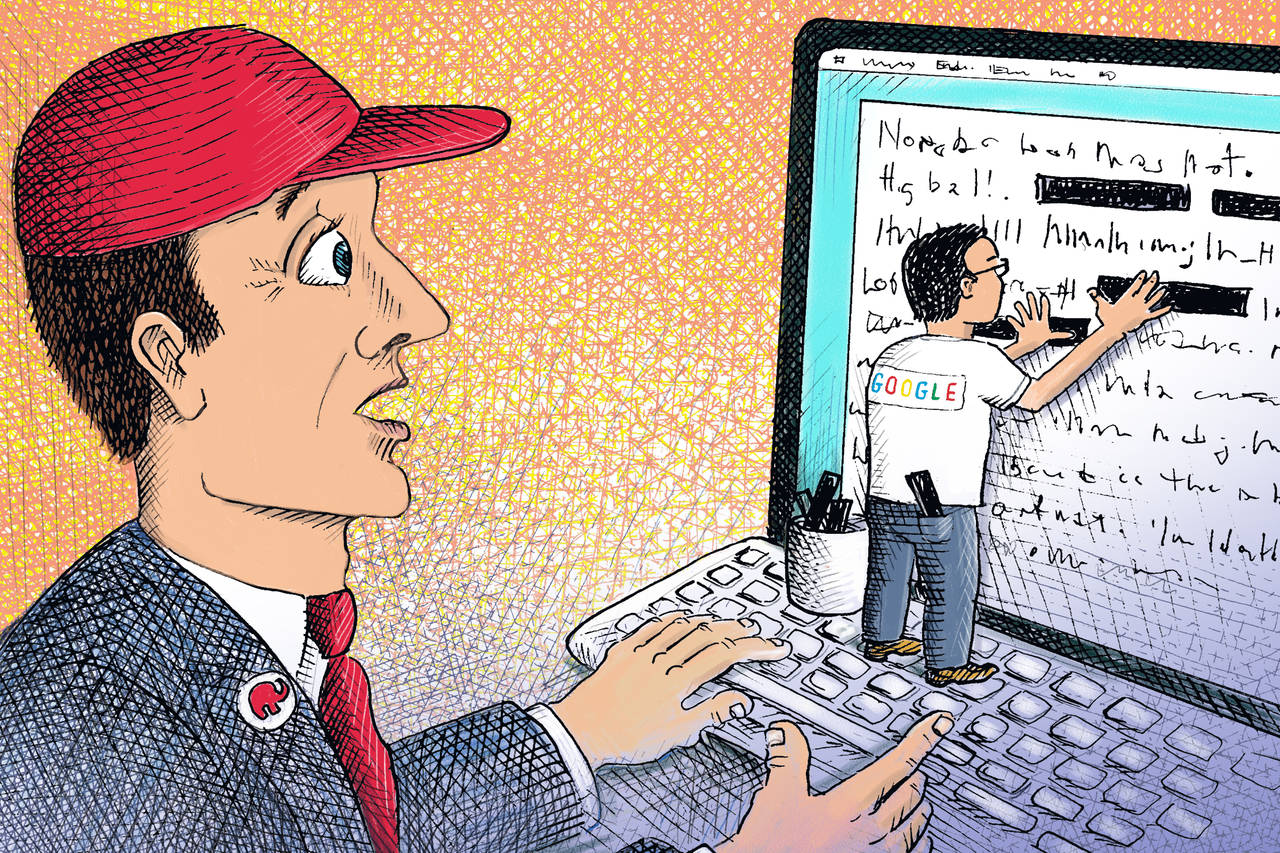

Regulating Online Content

With social media's rising popularity, people no longer use traditional news sites

to obtain information on current events. Instead, this information is obtained through

social media sites such as TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube, to name a few.

Facebook and Instagram are owned by Meta, and YouTube is owned by Google, which

together are the most notable tech giants.

Milton (2023) explains that the internet's disruption of the advertising-based

business model that had funded the news industry in Australia since the early 1900s was

in trouble. People would read the newspapers, publishers would sell their eyeballs to

advertisers, and advertisers would provide the cash needed to keep these newspapers

affordable. With the rise of the web and the monopolies accompanying it, this model

broke down. Google and Meta made online advertising far less lucrative. Today, the two

tech giants collect 90% of global advertising revenue, leaving little left to support the

media industry while enjoying the traffic from people seeking out the news. Australia

saw these detrimental changes to its news industry, with fewer people reading its

newspapers, revenue declining, and journalists laying off the masses. To remedy this,

the Australian government sought to rebalance the market by forcing Meta and Google

to pay Australian publishers for news linked on their platforms through legislation. The

law enacted by the Australian government in 2021 is called the Online Bargaining Code.

As we know, Canada has seen issues that are scarcely similar to Australia's.

Milton (2023) states that Canada was encouraged by the Australian Online Bargaining

Code and began to lobby for similar legislation in 2021. Today, we know Bill C-18, the

Online News Act, which was similar to the Australian model and threatened Google and

Meta with binding arbitration unless they came to private agreements with the country’s

news organizations.

Elistis who are tightly connected with the traditional news industry and

government, is concerned about the decreased gullibility of the upcoming generations.

Roderic Day (2022) explains that governments use news media as a tool to brainwash

and people no longer believe their lies. News media popularity threatens power elites

because we no longer follow the legacy media they use to spread their mass narratives.

Raising generations on social media only further contributes to the monopoly of social

media over news media, increasing the skepticism of our government's elites and

encouraging individuals to punch up instead of punch sideways for cultural issues. The

rise of new media is displacing news media and annihilating it. What is seen through the

uprising of new legislation being passed by governments is elite panic. Their

justifications for passing these legislations do not make sense, however, if you follow

their actions and motives, it all points towards them wedging themselves into these

social media areas where they can regain control. There are so many poked holes in the

evidence surrounding the reasons for the passed legislation that it does not make sense.

This leads to questioning why the governments are promoting and passing this

legislation. It is explained to be because of elite panic about losing their mass-narrative

control. Their plan works to limit access to these social media outlets to push individuals

back to their news media to force-feed them and brainwash them with their agendas.

Government Regulations

Governments frequently justify media regulations by claiming they are essential

for ensuring accurate news reporting and preventing misinformation. Roderic Day

(2022) critiques this approach, describing it as a tactic used by elites to maintain control

over public discourse, saying, "The news must be reported correctly, but let people enjoy

things—artistic freedom is sacrosanct.” He then identifies this claim as nonsense

liberalism. He is right, why does the government care about the artistic freedom of

individuals on social media? By justifying their actions in these ways, the government

can have more control over Canadian citizens, and their force feeds them their elitist

agendas. With the openness of social media, there is room for debates and skepticism to

band together to fight against these elitist agendas. Canadians were stepping on the

elitist's toes by blaming them for our cultural issues rather than blaming themselves. No

longer were people believing these “liberal delusions arising from the powerful justifying

their abuse,” so they had to backtrack, wedging their narratives back to Canadians (Day,

2022).

One example is Bill C-64 (Online Harms Act), which aims to combat hate speech

and misinformation. While proponents argue that such laws protect vulnerable

communities, critics warn that they grant excessive power to government bodies to

determine what constitutes "harmful content." The broad language of these laws risks

criminalizing legitimate dissent, leading to self-censorship and reduced political

engagement among citizens.

Legal Framework and Key Legislation

In Section 2(b) of The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, everyone has

freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and

other media communication.

In this section, we will look at specific legislation that breaches Section 2(b) of the

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom in (1) Bill C-11 Online Streaming Act, (2) Bill

C-18 Online News Act, and (3) Bill C-64 Online Harms Act.

Bill C-11 Online Streaming Act

Bill C-11, the Online Streaming Act, updates the previous broadcasting act to

include online streaming platforms such as YouTube, Netflix, and TikTok. The federal

government introduced the bill to modernize broadcasting regulations and ensure that

digital platforms promote Canadian cultural content. The legislation grants the

Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) expanded

authority to regulate online platforms, requiring them to promote and financially

support Canadian content.

Michael Geist (2024) explains that the Canadian government's decision to retain

an outdated model instead of modernizing the law has resulted in penalties for digital

success stories, “reflecting one of the world's most repressive online censorship

schemes.” Geist explains that there is little evidence supporting the need for mandated

discoverability on streaming services, yet this concept received strong backing from both

the industry and government. It raises questions about why discoverability became a

focal point for the Canadian creative sector when users can easily find Canadian content

by simply entering "Canada" in a search box or relying on algorithms (Geist, 2024).

Furthermore, Geist says there is ample opportunity for a modernized broadcasting law

that prioritizes consumers, competition, and a new generation of creators. Instead,

Canadians faced Bill C-11, which was less about genuine reform and more about panic

over the sector's viability. Despite Canadian culture's remarkable cultural and economic

significance, the government's reliance on unfounded fears may have introduced actual

harm, including decreased competition, increased consumer prices, and the potential

for a contentious trade battle with the United States (Geist, 2024).

Bill C-18 Online News Act

As the Government of Canada’s website explains, “News outlets play a vital role

in maintaining a healthy democracy,” saying how the news industry “provides citizens

with critical information that helps them fully benefit and participate in a democratic

society.” They explain how most Canadians get their news online, with online

advertising revenues in Canada being fourteen billion, with two platforms receiving

roughly eighty percent of these revenues. These two platforms are Meta and Google.

Furthermore, they explain that digital platforms earn billions in online advertising, but

their poor news outlets shutter each year due to the loss of advertising revenue from

Meta and Google. With the introduction of Bill C-18, they were able to level the playing

field, giving their power elites a fair chance against these tech giants. Bill C-18, The

Online News Act “aims to ensure that dominant platforms compensate news businesses

when their content is made available on their services.” Michael Geist (2024) explains

that Meta blocked all news links in response to Bill C-18.

Bill C-64 Online Harms Act

The Government of Canada’s website says that Bill C-63 contains measures that address

a range of harmful content online. This includes hate speech and hate crimes both

online and offline. They explain that to combat harmful online content properly, there

must be accountability to social media services accountable for reducing exposure to

harmful content on their platforms. Michael Geist (2024) points towards the similarity

between the government's justifications for Bill C-11 and Bill C-18 and now the new Bill

C-63 as another way of gaslighting since the response of Meta blocking Canadian news

media in response to Bill C-18, Canadian media bankruptcies and closures continue to

mount. Bill C-63, the Online Harms Act, offered a chance for a fresh start as the

previous two Bills were failures. However, the government ran into challenges as there

were harsh criticisms of the bill and “After a second briefing failed to quell the concerns,

the Minister and officials in the PMO have gone back to the gaslighting playbook by

dismissing the criticism as clickbait, suggesting they involve a misunderstanding of the

law” (Geist).

Historical Context of Censorship in Canada

In the next section, the paper will review the history of landmark legal cases and

legislation that have shaped free expression. Explored will be (1) the War Measures Act,

(2) the Constitution Act, and (3) R v Keegstra.

The War Measures Act 1914

Originally introduced during World War I, the War Measures Act granted the

federal government broad powers to suppress dissent and censor information. Its use

during the October Crisis of 1970 resulted in the mass detention of political dissidents,

illustrating how national security concerns can be leveraged to justify civil liberties

violations. The War Measures Act gave the government arbitrary powers to conduct the

war while protecting national interests. This allowed the executive to write new laws

without the need to go through Parliament. The Act restricted the civil liberties of

Canadians, imposing censorship. Those who went against and shared their views were

subsequently disciplined. Keshen (2015) said that censorship in Canada started by

focusing on telegraph messages to try to ensure that military-sensitive news was not

leaked. Censorship soon expanded to newspapers as leaked information, such as details

about the troopships, were publicly available. Problems have been raised however since

the bombarding of propaganda with no room for freedom of expression. There was no

way to freely debate the issues of the war. They used censorship strategically however, it

opened the doors later in history for a more intelligent form of the tool.

The Constitution Act

The Constitution Act of 1867 brought to Canada a constitution “similar in

principle to that of the United Kingdom,” though it was silent about liberties accruing to

individuals. The Supreme Court of Canada, which was also not a part of the Constitution

Act of 1867, which was made through organic statute, had seen cases and prepared to

enact laws regarding free speech. Roach and Schneiderman (2013) say that the Alberta

Press Case was quoted “free public discussion of public affairs, notwithstanding its

incidental mischiefs, [as] the breath of life for parliamentary institutions,” which would

have permitted substantial governmental interference with the operation of newspapers

in the province (p. 431). However, it was ruled that it was beyond the provincial

competence, for it curtailed the right of public discussion and trenched the federal

criminal law power.

R v Keegstra

James Keegstra, a teacher, was convicted under Section 319 of the Criminal Code for

promoting Holocaust denialism in his classroom. In his case, Dickson C.J.C applied that

not all expressions were equally deserving of consideration under Section 1 (Roach &

Schneiderman 2013, p. 435). Dickinson C. J. C found that “the promotion of hatred

‘propagate[s] ideas anathemic to democratic values’ does not advance the pursuit of

truth, and denies self-fulfilment to the targeted minority” (Roach & Schneiderman, p.

438). This case remains a landmark example of the tension between free expression and

public safety concerns in Canada upholding freedom of expression.

Conclusion

Censorship in Canada has evolved from wartime restrictions to modern

regulatory frameworks governing digital spaces. While legislations such as Bill C-11, Bill

C-18, and Bill C-64 are justified as protective measures, they often result in greater

government control over the information Canadians can view. This consolidates media

power rather than ensuring press freedom as guaranteed in Section 2(b) of the Charter.

The government's increasing control and the rise of traditional media run by

government elites raise concerns about transparency and the Canadian government.

As highlighted by experts like Christine Van Geyn, the emergence of new

censorship tactics demonstrates how legislative measures can stifle dissenting voices

under the guise of public interest and societal cohesion. The challenges regulated

professionals like Dr. Jordan Peterson face underscore the precarious balance between

upholding free expression and maintaining professional standards.

As Canadians increasingly turn to social media platforms for news and

information, the traditional media model is disrupted, leading to significant

implications for democracy and public discourse. Ultimately, the true motive behind

media legislation in Canada should align with the principles of democracy, ensuring that

the fundamental rights of citizens to freely express and access a broad spectrum of ideas

remain protected and that censorship and governmental control are absent. Only by

ensuring open access to diverse perspectives can Canada uphold its commitment to

democracy and free expression.